Project supervision

Working with Liyan was always a pleasure: She was smiling and enthusiastic all the time, and very pedagogue. I was impressed by her drawings to explain scientific notions. She was able to illustrate anything, even very complicated concepts ! It was one of my first experience in the lab and it’s thanks to her that I got the envy to keep going in this path, so thank you Liyan :)

During my PhD, I had the privilege of supervising three exceptional students for their bachelor’s and master’s projects. These students were, in many ways, textbook-perfect: punctual, diligent, and quick learners. They required minimal oversight, yet this allowed us to focus on broader, more nuanced aspects of scientific research. Together, we navigated the challenges of transitioning from a student mindset to a researcher mindset.

Guiding the Transition from Student to Researcher

Research is fundamentally different from coursework. It involves exploring questions that don’t have clear, predefined answers. One of the key lessons I emphasized was the need to make judgment calls: determining when something is “good enough” versus when to dig deeper.

I emphasized that a failed experiment doesn’t equate to personal failure. They learned that sometimes, even when all steps are executed perfectly, results may still not align with expectations. The key is to approach this creatively and critically: What are the possible next steps? What might the results mean? To instill this mindset, we frequently discussed possible outcomes for their experiments—those confirming hypotheses, those rejecting them, and those indicative of technical issues. I guided them by modeling the thought processes I use to troubleshoot and plan next steps, gradually helping them take ownership of these strategies.

Encouraging Sustainable Scientific Practices

Another crucial aspect of mentoring was teaching sustainable research practices. The excitement of discovery can sometimes lead to overworking or losing focus. I encouraged my students to pace themselves, reminding them to take breaks and approach their work with balance. If things weren’t going well at the end of the day, I’d tell them to go home. There was no sense in stressing over it for two more hours when they could instead relax, recharge, and return fresh the next day. Research takes too long too do it all in one breath.

Developing Presentation Skills

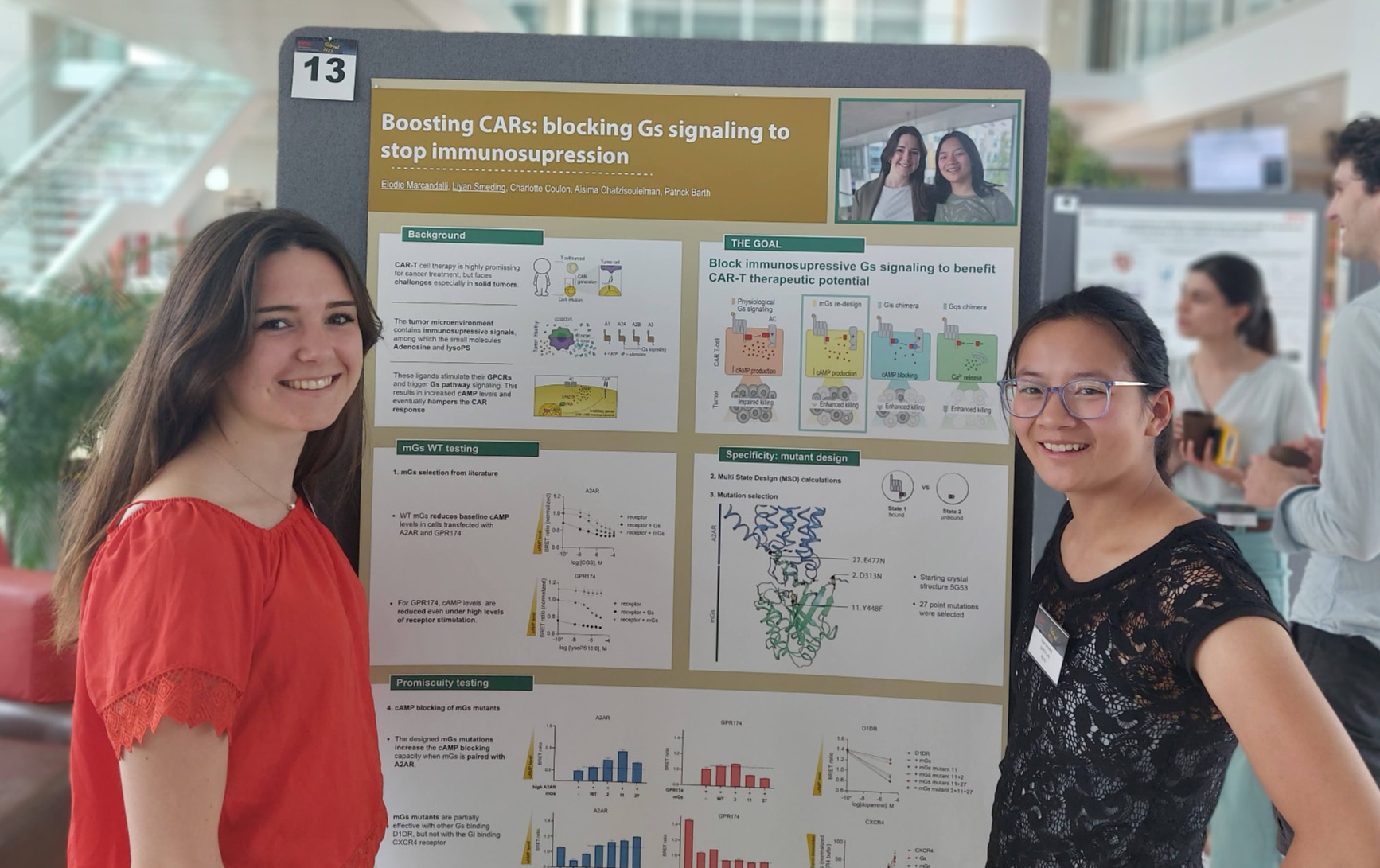

Presentation nerves were another area of growth. At the end of their internship, the students were required to present their projects during a lab meeting, including to our professor and the rest of the team. Naturally, this was nerve-wracking.

One interaction that stands out occurred the day before a student’s presentation. I had just delivered a poster pitch myself, and I admitted to her later that I had been nervous too. Presenting in front of people outside the lab, especially fielding unexpected questions, can be daunting. I didn’t show my nerves at the time—it wasn’t overwhelming—but I wanted her to know it’s possible to feel nervous and capable at the same time.

When we talked, she was psyching herself out, repeatedly saying how nervous she felt, which only heightened her anxiety. I stopped her and said, “This feeling? It’s growth. I felt the same yesterday. It doesn’t stop—not if you keep challenging yourself. But that’s not a bad thing. Things can be scary, and you can still be ready for them.” I reminded her of how well she’d prepared, how capable she was, and how I’d seen her presentation and knew she could do it. Then I said, “Now stop psyching yourself out and breathe.”

This conversation helped her center herself, and she delivered a confident and compelling presentation. Experiences like these remind me how important it is to normalize nerves and teach students to embrace them as part of the growth process.

Post a comment